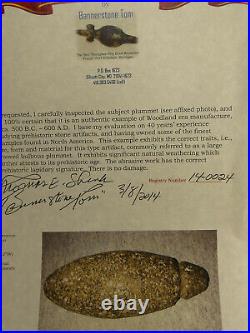

X-RARE Osage Nation 4.66 Shaman’s Charmstone with150+ Petroglyphs! Missouri. COA

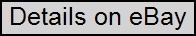

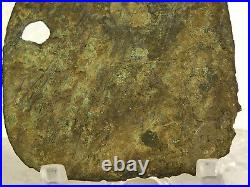

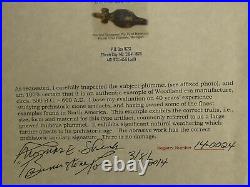

Ancient Art, Antiques, & Fine. Native American Osage Nation Shaman’s Charm Stone. An Estimate 150+ Incised & Painted Petroglyphs. Spirit Animals, Buffalo, Elk, Birds, & Mythical Creatures. A Record of Shaman’s Many Vision Quests. Woodland Period: Great Plains of Missouri. I certify that this ancient artifact was legally collected on private land with the owner’s permission in Missouri, during the mid-20. Century, and has been in a private collection since that time. It was a surface find and no caves, graves, or mounds were disturbed. This is an opportunity to legally own stunning, ancient Native American artifact that is estimated to be about 2,000-years-old! Osage Grooved Shaman’s Charmstone with an Estimated 150+ Petroglyphs. 4.66 (118 mm). Or 1.69 lb. “Bannerstone Tom” Registry Number. As found, museum quality, with 150+ original stone pictographs (called petroglyphs) incised and painted onto the stone. Much of the black painted pictographs on the rough, hardstone surface is no longer visible, thus making it difficult to determine the shape of the image they painted. NO repairs or restorations. This superb, museum quality Charmstone/Divining Amulet is about 4.66 long and was discovered in the late 1800s in Missouri, and has been in a family collection until recently. It documents an Osage Shaman’s Vision Quests and/or the Creation Legends of the Osage. For the advanced collector of the rarest, Native American artifacts! As one of the RAREST Osage Nation charm stones in existence, this brown, conglomerate, hard-stone artifact still has remnants of a blackish paint from the pigments used to on this divining stone. This black paint is most noticeable along the sides of the charm stone, where it appears to show a graphic image of a mythical creature and/or the deity ” Maun, ” the Earth Maker. Each Osage village had a number of ” wa eghi, ” or headmen, who acted as shaman and leaders in such matters as war, religion, administration, and medicine. This charm stone would have been made and blessed by one of them, and included in his Medicine Bundle for his personal use only. Shaman did not share their sacred paraphernalia. Although the spirits appeared to shaman in their vision quests in either human or animal form, they could sometimes appear in strange forms that are more difficult for us to interpret and understand. Each vision was a highly personal experience, and although it would have been interpreted and explained by a shaman, its full significance might only ever be known to the visionary. Over 150+ of the petroglyphs on this charm stone exhibit mythical, human, bird, and animal characteristics, but their exact meaning is unknown. As you read my English translation of the pictographs/characters on this Native American, Osage People charm stone. You are among the first people in the world to read them, as the petroglyphs on this charm stone have never been documented or deciphered before-in any language! Some historians have estimated the Osage population on the Great Plains in Missouri, before first contact with Europeans at between 4,000 and 6,000; whatever their number, it was sufficient for them to maintain control over most of what is modern-day Missouri, Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. This Osage Shaman’s charm stone has an estimate 150+ tiny, incised and painted, stone carvings (petroglyphs) on all sides of the tear-drop shaped Shaman stone! The incised petroglyphs are exceedingly small-most less than 3mm long! They all seem to reflect on a Plain’s Indian, Shaman’s Vision Quests, as it depicts him riding horses and buffalo, with dozens of Spirit Animals and mythical creatures surrounding the Shaman, who is in a trance and Astro-traveling. See below for details. A spiritual people, the Osage Indians of the Central Plains were excellent hunters and fierce warriors. Their religious beliefs were based on Wah-kon-tah, (also ” Wakan Tanka “) the Great Spirit-also the Great Mystery Spirit or Great Power. In one Creation legend, the Osages believed that the People of the Sky (Tzi-sho) met with the People of the Earth (Hun-Kah) to form one tribe, the Children of the Middle Waters (Nee Oh-kah-shkahn). The Osage were a highly spiritual people who worshipped a single deity- ” Maun, ” the “Earth Maker” or Creator. Theirs was a clan-based society, with each clan springing from a benevolent spirit animal related to the Creation of the World. The Osage lands were a place of great, ritual ceremony and spirit quests. Various chroniclers and eyewitnesses have stated that few Osage stood less than 6 feet in height, while many reached a well-proportioned 6½ or 7 feet tall. In his History of Early Reynolds County Missouri, James E. Bell attributes their height, strength, and physical courage to tribal marriage practices. The. Mightiest warriors got the tallest and strongest girl-plus all her sisters. As one of the RAREST Osage charm stones in existence, this brown, conglomerate, hard-stone artifact still has remnants of a blackish patina from the pigments used to on this divining stone. This black paint is most noticeable along the top and base areas where it appears to show a graphic image of a mythical creature and/or the deity ” Maun, ” the Earth Maker. This charm stone would have been part of a Shaman’s Medicine Bundle that contained tokens representative of specific aspects of the vision. The idea of the shamanic journey as envisioned by the Plains shamans, is one of a continual quest for sources of power. Each Osage village had a number of ” wa eghi, ” or headmen, who acted as leaders in such matters as war, religion, administration, and medicine. A hereditary position, headmen were looked to for guidance and direction and were required to possess courage, kindness, compassion, impartiality, and the ability to always light the proper course by personal example. Although the wa eghi were not chiefs per se-a distinction that would later confuse and confound European arrivals-they were singly and collectively responsible for maintaining the order of the community. In Plains ideology, the Sacred Journey is likened to a spinning hoop and everything in nature and in man is conceived as circular in motion and in form. This philosophy is sometimes referred to as the Sacred Hoop. This concept of circular motion is reflected in the items their shaman utilized during their vision quests. This charm stone is tear-shaped with a suspension groove, or “top hat” carved in the pointed top that is about 24 mm wide. {See photo # 9}. This groove would have allowed a small vine or similar string-like object to be tied around the top of the charm stone and allow it to swing and twist randomly back and forth at the will of supernatural forces. Skilled shaman would assess its rotation or swing to answer “yes-no” questions or interpret these motions and decide on an appropriate course of future action. Several of the petroglyphs on this charm stone exhibit human, bird, and animal characteristics, but their exact meaning is unknown. Before Europeans came to the Americas, Osages obtained food by hunting, gathering, and farming. Osages hunted wild game such as bison, elk and deer. There were two bison hunts a year, one in the summer and one in the fall. The goal of the summer hunt was to obtain meat and fat. The purpose of the fall hunt was to obtain food, but also to get the thick winter coats of the bison for making robes, moccasins, leggings, breechcloths, and dresses. Although only the men hunted, the women did the work of butchering and preparing the meat, and tanning the hides. The word “Missouri” often has been construed to mean “muddy water, ” but the Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology has stated it means “town of the large canoes, ” and authorities have said the Indian syllables from which the word comes mean “wooden canoe people” or he of the big canoe. Osage Petroglyphs & Pictographs. In general, petroglyphs are pictogram and logogram images created by removing part of a rock surface by incising, picking, carving, or abrading. Outside North America, scholars often use terms such as “carving”, “engraving”, or other descriptions of the technique to refer to such images. Petroglyphs are found world-wide, and are often associated with prehistoric peoples. What makes this Shaman’s charm Stone incredibly RARE is its large number of an estimate 150+ pictographs. Some graphics are larger, faintly painted characters of mythical creatures-some as large as 57mm long-while the vast majority of characters are much smaller, incised characters that are smaller than 3mm! These petroglyphs can be seen on all sides of the charm stone or amulet. The Osage had no written language that we know of, but they did use both pictographs and petroglyphs that have been found on the walls of the hills caves where their Shaman went to communicate with the Earth Maker and other spirits. Osage shaman are thought to have experienced these visions after prolonged periods of thirsting and fasting, and by sleep deprivation. Reportedly, some shaman also used the regular influence of smoke offerings and even psychotropic drugs to. Influence supernatural beings; bring about successful hunting and fishing; influence forces of nature to benefit the tribes; and to intervene in human affairs to heal and protect. During vison quests, Osage Shaman would use the smoke from their pipes (which they always carried) to make the breath visible. ” and thus enable the person’s ” nagi to travel in visible form to meet their Spirit Animals and be shown some of the secrets of the spirit world. Based upon the large, horned animal petroglyphs, I have identified various animals and the human stick-figures surrounding them and I believe an Osage Shaman may have used this charm-stone as a powerful divining tool to predict or to bless a future hunting parties on multiple occasions. As stated above, I believe a Shaman would have divined the unknown by hanging it from a vine and then accessing its rotation or swing to: answer questions, ask for guidance from the Great Spirit, or predict the future. I assume all responsibility for the information contained in this description and for the English translation and transcription of the ancient Chinese graphic characters. Furthermore, I prohibit the further dissemination of this information in any written, video, or electronic format without my expressed, written approval. Experts believe that Osage pictographs and petroglyphs made by shaman on their personal objects in their Medicine Bundles often represented a complex, supernatural world that are not easily understood by modern man. Therefore, some of the petroglyphs depicted on this charm stone are not easily translated into single nouns, verbs, or modifiers. At first, these marks appear to be just tiny dings or differential weathering. They are slightly darker in color than their surrounding lighter colored stone. But under 10x-20x power magnification, one can clearly see tiny, pictographic, stick figures and characters that are images of people, animals, fish, stars, and unidentified objects or mythical beings. The images range from about 57mm long to. Here are just a few of the petroglyphs one can see under 10x magnification. The largest image was painted in black on this charm stone measures about 57mm long. Although faded with time and natural weathering, I believe it may be the image of the mythical Great Spirit, who is depicted here with outstretched wings. Wah-kon-tah, (also “Wakan Tanka”) the Great Spirit-also the Great Mystery Spirit or Great Power. In the shaman’s language, Wakan Tanka is referred to as Tobtob Kin. ” A direct translation of this is “Four-Times-Four Gods. The Osage held that the magenta blossoms of the Redbud Tree were emblematic of the eternal renewal of all life and contained the life force of the tree. They used ash from Redbud wood as a sacred paint, and it was likely the paint they used on this sacred charm stone. {See photo # 5}. Shaman riding on horned bison, who is shown walking to the right in this photo. To the Osage, the shaman WAS these animals, and not merely a human impersonation of the animals. {See photo # 10}. Shaman in the middle of a ring of Spirit Animals during a Vision Quest. In the same photo, there is a tiny shaman who is less than 2mm tall! He is circled in this photo and is clearly pictured with an elaborate, braded, top-knot style that was unique to each shaman. Hair was considered to be the seat of the “soul” or spirit. He is shown riding on the back of an animal. A depiction of a shaman in elaborate costume, who is holding a rattle in his hand. And there are an estimated 150+ other petroglyphs incised into this fabulous charm stone. You have just read my English translation of the pictographs/symbols on this Native American, Osage People charm stone! Shamanism in North America. Missouri Department of Natural Resources. A History of the Osage People, by Louis F. The Osages: Children of the Middle Waters, by John Joseph Matthews. Osage Life and Legends, by Robert Liebert. 1 and 2, by George Catlin. Tixler’s Travels on the Osage Prairies, by John Francis McDermott. The Imperial Osages, by Gilbert C. Killers of the Flower Moon, by David Grann. Macro Photos taken indoors under magnification to show the detail of these tiny petroglyphs. The stand and ruler are not part of the sale, just there so you can better judge the size and to capture the beauty of this ancient work of art. Each object I sell is professionally researched and compared with similar objects in the collections of the finest museums in the world. When in doubt, I have worked with dozens of subject matter experts to determine the condition and authenticity of numerous antiquities and antiques. All sales are Final, unless I have seriously misrepresented this item! Please look at the 4x and 20x macro photos carefully as they are part of the description. Member of the Authentic Artifact Collectors Association (AACA) & the Archaeological Institute of America (AIA). US Buyers only for this SUPER RARE piece of Native American History.